My hands flush red in the cold. A rare snow has fallen: powdery, soft, and bright. It gathers on the toes of my boots as I shuffle towards the park. I have missed the white snow so much through this year, missed the glare of light on the land.

Winter is about these brief encounters with the outdoors. There is a sense of accomplishment from even a brief journey outside. But as much as my walks grow shorter and my pace quicker, I try even harder to notice the season’s changes. Winter isn’t flashy, and the life that thrives in the cold season isn’t always easy to spot. But close attention to the modest corners of the city, park, or forest can be rewarding.

As early as November, frosts might harden the ground. I try to notice them as I walk: the crunch of frigid grass underfoot, and the snapping sound made by mud that has frozen tight. So often it rains: clay mud sticks on my winter boots and sucks my feet to the ground as I walk, while sandier, loamy soils bounce like a soggy sponge.

What is the ground like where you walk? Does it offer clues for the geology underfoot?

Even indoors, as I warm my hands on a mug of tea, I can gauge the weather by the sky: the high, feathered clouds tell me it is likely to be fair if cold. Low, grey clouds can signal fog or rain. And of course, on days when the sky is painted entirely in deep grey, I don my weatherproofs.

I delight in searching for the geometry of winter on windows and on water. On very cold days, single-glazing may frost over, sending fine filaments of white across the windowpane. They look perhaps like fronds of fern.

After clear and chilly nights, look for hoar frost—a hairlike layer of ice that forms on leaves, trees, fenceposts, and other thin surfaces. It looks a bit like fuzz but can also be longer, like strands of hairy ice. As you pass puddles or streams, look for the brittle shards of ice that tighten around the edges. Do they freeze in a particular pattern?

Beneath fallen wood and the stumps of old trees, mosses and lichen are winter’s true stars: ever green and even brighter after rain. They force me to look closely, at eye level, and to adjust my sense of scale.

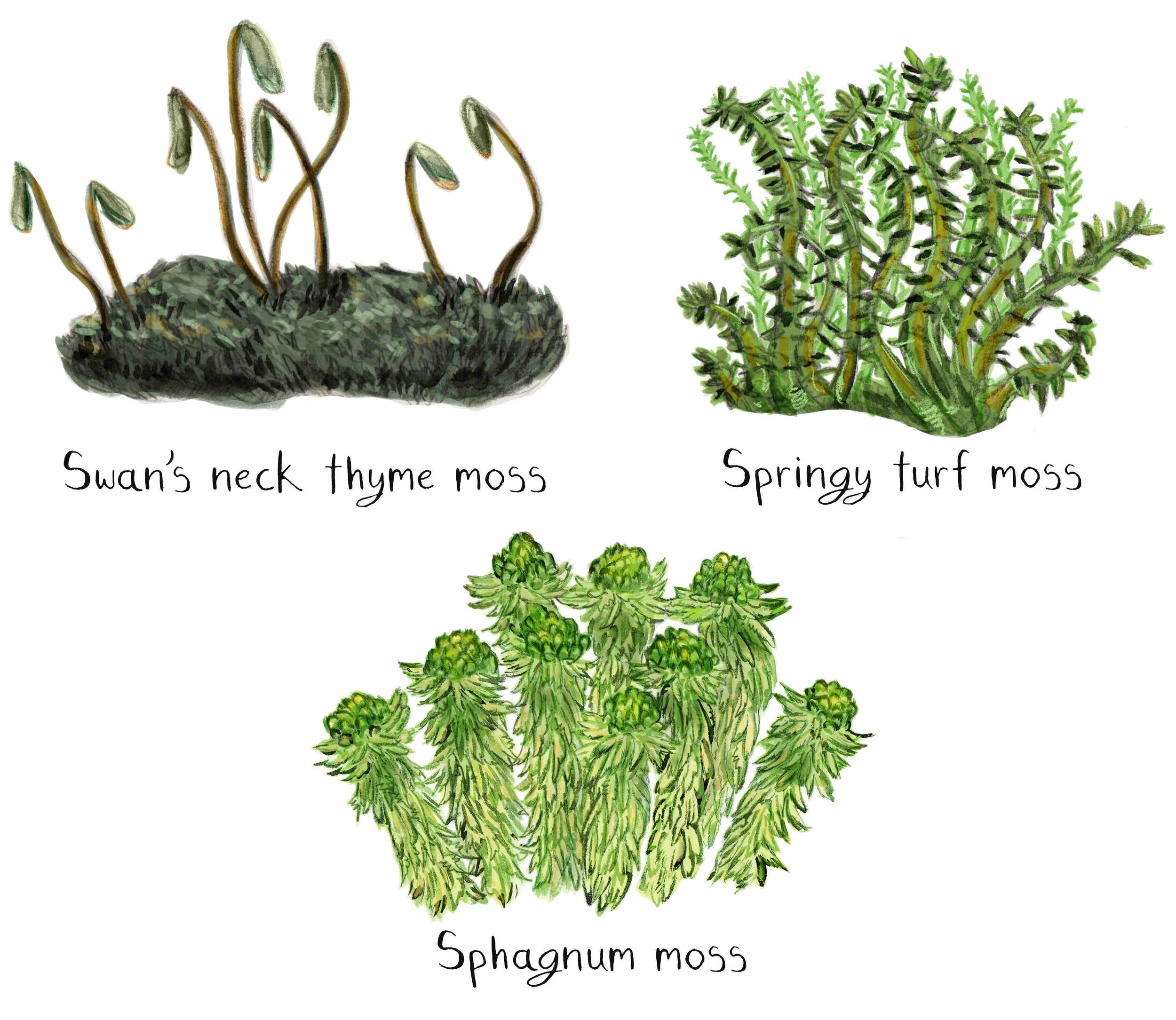

When I spot mosses on garden walls, bus shelters, or wood, I try to discern if it’s just one type of moss or many. I look for the long stems of swan’s neck thyme moss, which grows just about anywhere in the city or country. The orange-tipped stems grow from a low carpet of thyme-like leaves. It’s from this tiny height that the moss distributes its spores.

Springy turf moss with its red-orange stems might appear in a lawn or a park, especially where the drainage is poor. And sphagnum moss, with its green-peach waxy sheen, may cover the ground on spongey heaths and moors. Peatlands do more than we may imagine: they are historic ‘carbon sinks’, holding huge amounts of climate-changing carbon deep in the soil.

Look out for moss in everyday places: on brick walls and railway bridges, on rooftops and windowsills.

The street trees where I live are all bare of leaves in winter. I miss the fullness of summer, but I see this quiet period as an opportunity to hone my skills for recognition: can I tell the trees apart by just their bark? Can I find clues in the leaf litter leftover from autumn?

Plane trees, commonly planted along busy roads, are easily recognised by their camouflage-hued peeling bark. Beeches typically have smooth, unblemished bark, while birches have patchy or peeling sheets of white bark. Deep, vertically-ridged bark can mean oak, while smooth bark freckled with horizontal stripes can be cherry or plum.

And though the migrant birds are away in these darker months, plenty of birds remain. I look to the water to see the most: ducks huddled in sheltered corners of ponds and rivers, and swans that stay in city parks.

Coots and moorhens are very common sights at ponds, lakes, rivers, and reservoirs. Both look slightly smaller than ducks and are covered in dark feathers. You can tell them apart by their beaks: moorhens have a red face and beak, while coots have white faces and beaks. If you spot either, it’s worth trying to get a peek at their feet: both have comically large, dinosaur-like legs, with the coots’ feet more distinctly webbed for swimming.

Some simple ways to notice the winter:

Try to identify the trees nearest to where you live: Can you find trees with smooth bark as well as some with ridged bark? How about peeling bark? If you look to the ground, are there dried leaves surrounding it? These can offer clues about what kind of tree you’ve found.

Can you spot mosses growing on objects like walls, ledges, even the edges of the pavement?

Try to count the many types of birds you see in winter: in the cities you’ll notice pigeons, magpies, and crows, but also ducks, swans, robins, and if you’re lucky, herons.